Special Report: Baseball’s Coming Artificial Intelligence Revolution

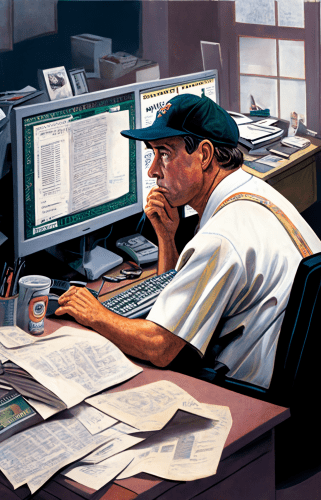

All images in this story were rendered using the artificial intelligence program Midjourney.

The year is some time in the distant—but not too distant—future. The general manager of the London Werewolves is working hard to bring the first World Series title to a team outside of North America.

And utilizing artificial intelligence in a wide variety of ways is part of the GM’s plan to lead the expansion team to success.

Every morning, the GM wakes up to a summary of all of the notable happenings from the organization’s minor league games. A program gleans the most pertinent information—both good and bad—from what happened the night before. And that isn’t just a recitation of the box scores.

The summary is compiled by searching through all of the tracking and biomechanical information for every player in every moment of every game. It’s petabytes of information that is gathered every day, but the program has been trained to find the actionable, useful pieces of info in a sea of data.

That same data is fed into the team’s projection systems, providing updated player valuation and statistical projections that weigh hundreds of data inputs.

Whenever a player hits the waiver wire, or a trade is offered, the AI-driven projection system weighs in on how the player should be valued.

At the same time, the pitching coordinator is checking the upcoming offseason’s individualized throwing programs for the organization’s 85 pitching prospects. Years ago, putting together those throwing programs took many hours of work, but now there is a program that knows the individual needs and development plans of every pitcher in the organization.

Instead of spending hours writing those plans, the pitching coordinator simply needs to confirm that the computer-generated pitching plans are exactly as desired.

Whenever a pitcher takes the mound during the game, the eyes in the sky—more accurately the high-speed cameras that ring the entire stadium—watch every pitch both in the game and in the bullpen at 1,000 frames per second. A veteran pitching coach might be able to notice if a pitcher is not finishing his delivery the same way as usual, but the computerized vision model has been trained to watch dozens of different metrics every time any pitcher throws a pitch. It compares what it sees to that pitcher’s normal delivery and sends alerts if a pitcher’s delivery is abnormal in a way that could increase a risk of injury.

The amateur scouting team is already looking ahead to next year’s draft. The team still has area scouts and crosscheckers who attend games, write reports and gather intel on makeup and other items. But their travel schedules are now preplanned by AI, which maps out the most efficient way to see the most players with the most efficient travel. Their reports, as well as all biomechanical information, game-tracking information, medical reports, psychological testing and every other piece of information gathered about any draft-eligible player is fed into massive databases. Next year, the board will, for the first time, be lined up by AI.

The GM has signed a deal with Amazon for a documentary series along the lines of the Formula 1 production “Drive To Survive,” that will allow Amazon Prime Video to document the team’s entire draft process. Then a series will air about London’s draft, powered by Amazon Web Service’s AI services.

The promise of seeing a computer line up the draft board enticed Amazon to make the offer. That sponsorship and the contract to air the documentary series on Amazon will help pay for the draft’s signing bonuses, which makes London ownership happy.

To sell tickets, the team’s marketing decisions are often driven by AI’s suggestions. Even more importantly, ticket pricing is driven by AI. The computer programs can determine ticket demand and scarcity hundreds of times a day using not just information like the quality and fan interest in the opposing team, but also weather, other events in the same town, secondary ticket market information and dozens of other factors. Much like an airline seat, the same row at the ballpark may have eight different fans who paid eight different ticket prices.

The system has changed in another way as well.

Whereas MLB teams used to have front office officials interview dozens of potential entry-level job candidates at the Winter Meetings, now an AI program conducts the first waves of interviews. Only the top candidates advance to speak to a live human in the final steps of the decision-making process.

All of the above is hypothetical, but none of the above is impossible, not as AI becomes more and more pervasive in baseball.

This theoretical glimpse into the future was compiled by talking to AI experts and technologically savvy people working in baseball.

“Usually there is a stark divide in how my friends in Silicon Valley talk. Not on this,” Driveline founder and CEO Kyle Boddy said. “I have multiple friends at Google, Microsoft and Amazon who left for less money to work in AI. They are voting with their feet. They are saying, ‘This is it.’ If anything can be bigger than the internet, this can be it.”

We stand on the potential cusp of the next revolution in baseball, as the data age morphs into the AI era.

Over the past six months, artificial intelligence has become a buzzword across the globe. The arrival of Chat GPT’s easy-to-use interface to access a robust, large- language model has demonstrated that these types of programs can produce content that seems as if it were produced by a human.

That is AI—but it’s only one aspect of AI.

Even defining artificial intelligence can be tricky. It’s a term that can cover a wide array of different approaches computers can use to answer questions and solve problems. There are language-learning models, such as ChatGPT, that ingest massive amounts of written data. That data allows the program to predict word by word a response any questions it’s asked.

Other machine-learning programs can try to use pattern recognition to develop computer vision. Other programs can take large amounts of data and try to “learn” how to find the best approaches to win a programmed task. That’s how computers have gotten to the point where they can beat the best chess masters in the world in head-to-head play.

While there are concerns raised about how far AI will eventually go, and whether at some point it could “escape” the control of humans, the more immediate questions revolve around whether it can be accurate and reliable. With the right prompts, ChatGPT can save hours of work, it can help write computer programs and database queries as well as provide in-depth answers to whatever questions one can imagine.

As a text-prediction tool, it’s always working to try to predict the next word in a sentence or a paragraph. It doesn’t necessarily verify that the next word is accurate, just that it is the best prediction.

So when Baseball America asked “who has thrown the fastest pitch in MLB history?” ChatGPT responded that “The hardest pitch ever recorded in an MLB game is 105.1 mph (169.1 km/h), thrown by Aroldis Chapman of the New York Yankees on September 24, 2010. Chapman has consistently thrown some of the fastest pitches in MLB history, with multiple pitches exceeding 103 mph.”

The velocity, as measured at the time, and the date were both accurate, but ChatGPT inaccurately reported that Chapman played for the Yankees at that time, when he was actually pitching for the Reds.

The current state of much of AI should be viewed as a useful tool, but one that always has to be closely scrutinized.

“(ChatGPT) is a very confident teenager, and much like a confident teenager, it doesn’t do math,” said Corey Patton, CEO of Pramana, a natural language processing company, which is another form of AI. “As Ronald Reagan said, ‘Trust, but verify.’ ”

AI is actually prevalent in all our lives already. If you ask your phone to call a number, the programming that allows the phone to hear your voice, understand what you are asking and carry out your request is a form of AI. When your calendar program prompts you that you have a Zoom meeting—and provides a list of useful documents to prepare—that’s another form of AI. And when you blur your background on the Zoom call, that’s AI at work again.

So AI is already part of baseball, but thanks to steady improvements in processing power—especially the parallel processing power created by video cards first developed to power video games—increasingly powerful AI tools are coming to baseball.

Baseball is a sport where dozens of professional teams around the world, hundreds of colleges, thousands of high schools and various other organizations are all looking for an edge. AI will be a tool in a savvy team’s toolbox. Or more accurately, it will be a full tool shed.

It’s the next step in the revolution that has already transformed baseball.

At the turn of the 21st century, baseball was a sport that largely remained in an analog era. Data was scarce, and many of the competitive advantages that separated teams were based around individuals. The insights of a general manager, the acumen of a veteran scout or the ability of a pitching coach to help a pitcher improve made the difference between one organization and another.

Data added a new layer of potential competitive advantages. In the past 20 years, teams have found a way to win by gleaning the significance of data before other teams did.

When TrackMan began proliferating in baseball in the early 2010s, teams began to realize that pitchers with higher than average spin rates often correlated with increased success at missing bats.

The Doppler radar-based system of the time measured only a pitch near the release point and then extrapolated its movement. In reality, the spin rate metric itself was only semi-useful, and there were plenty of examples of players whose above-average spin rates didn’t correlate with success or failure. It was the best available tool at the time, however, so teams that used it got ahead of teams that didn’t.

As soon as newer pitch-tracking devices began to be able to measure the complete movement of a pitch from release to the catcher’s mitt, more advanced measurements like induced vertical break—the measurable ride on a fastball—and vertical approach angle became available.

With that, teams moved on to trying to draft, sign or trade for pitchers who had abnormally low VAAs or extreme amounts of IVB. At that point, a team focused on spin rate would have fallen behind teams that were finding insights from more advanced datasets.

Similarly, when exit velocity started to be measured, there was no owner’s manual to tell teams whether average exit velocity, median EV or maximum EV was the most useful indicator of future offensive success. Before long, teams began to figure out that the measure of a player’s 90th percentile exit velocity was most useful. That was low enough to filter out misreads and outliers, but high enough to demonstrate the upper end of a player’s power potential.

The advantages teams gained by figuring out the valuable insights from those metrics quickly disappeared. New insights around baseball have a habit of quickly turning into accepted conventional wisdom.

So there’s a neverending race to try to figure out the next insight before 29 other MLB teams. And that’s one of the ways AI may prove helpful.

Since AI is comfortable working with massive datasets, it can more quickly identify the most useful metrics. With proper prompts, programs can sift through mountains of data quickly, and in doing so may find insights that would take humans longer to glean.

In a sport where the early adopters gain an advantage, AI has the potential to quickly help teams. AI will also provide opportunities to handle many repetitive tasks.

What AI is unlikely to be able to do for a while, however, is handle tasks without human supervision. If the data revolution led to teams hiring scores of programmers and quantitative analysts in roles that never existed in baseball before, it also led some teams to cut back on the number of scouts they employed. A number of teams decided to do both to reap the advantages of both approaches.

As AI programs become more and more prevalent, they may spell bad news for the entry-level programmers who have benefited during baseball’s current era. One of AI’s first killer apps is its ability to produce reasonably solid code for basic programming needs.

In the past, a GM might ask a senior member of the research and development team to find an answer to a baseball question, and then that senior member would delegate the programming to a junior member of the R&D team. Now, the senior developer may simply ask AI to write a program. That program would need to be vetted and tested by the senior developer, and they may notice areas of programming to tweak or clean up.

Will AI help the Werewolves win a World Series? Maybe. If it does, other teams will quickly follow. It’s the way baseball—a copycat sport—works, and the possibilities that could come from AI will make it hard for teams to ignore.

Comments are closed.